Jishnu Mohan

Homepage

On Execution

by Jishnu

At the launch of The Birthday Book, the editor paid Aaron Maniam1 what I considered the greatest compliment ever. He said, and I paraphrase, that “Aaron’s the guy to go to if you want to actually realise one of your half-baked ideas”. That’s so beautiful.

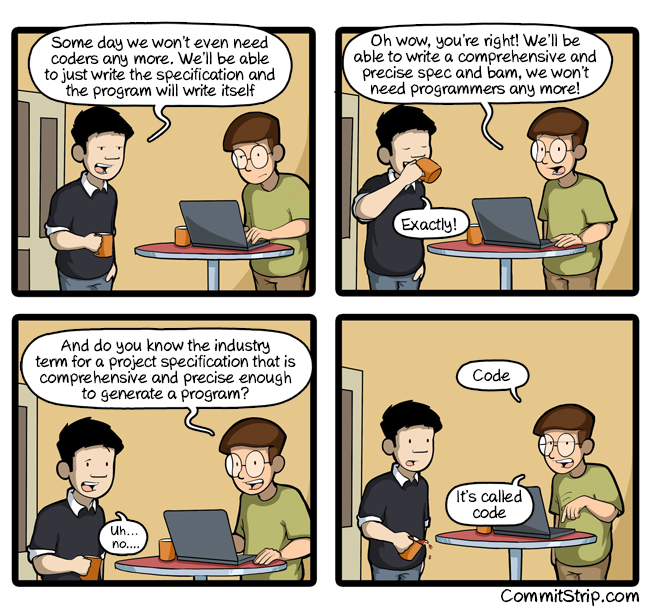

Ideas are cheap. Everyone has ideas. If you’ve fallen victim to the Disruption Virus going around, you probably have a dozen before lunchtime. Sure, good ideas are rare, but telling good from bad at the half-baked idea stage might as well be divination. Ideas are overrated. Execution, on the other hand, is criminally underrated. Going from idea in the head to actual working thriving product/ system/ event is the most important journey there is.

This might be surprisng because ‘execution’ in everyday usage covers two broadly different tasks. The more mundane interpretation of execution is the boots on the ground, rubber meeting the road, grimy grunt work. It’s the nights spent polishing your slide deck and fine-tuning your financial projections, the hours practicing your elevator pitch into the mirror, the coffee ingested trying to find that elusive Heisenbug which periodically cleans out your database, [insert drudge work in your chosen profession / field here]. Sure, that’s execution, and sure, that’s important. However, you’re probably a well oiled machine at this. You’ve invested enough time in projects and learning to be completely in your element doing these things to perfection. (if you were doing more interesting things in school, don’t worry, these skills aren’t in too short a supply).

The more interesting part of execution, and by far the rarer skill, is the jump from an audacious oh-wouldn’t-it-be-cool-if intimidating dream to actual concrete managable tasks. This is the alchemy that resolves the annoying paradox of ‘what’s doable is not interesting, and what’s interesting is not doable’. If you’re an average colour-within-the-lines product of the System as I am, you’re completely unprepared for this. School projects have always been managable enough that breaking them down have either been fairly trivial or have featured significant assistance and feedback from professors, seniors and peers.

A friend pointed out to me that the problem is compounded for those of us who were blessed enough to not to be challenged much in our early schooling. We coasted on intuition and natural ability, missing the opportunity to cultivate good habits of process and discipline. It’s no wonder therefore that when faced with challenges beyond the scope of our intuitive ability, we freeze up or flail aimlessly. (Credit also goes to the first articulation of this idea I was exposed to, Eric Raymond’s advice to Linus Torvalds regarding a Linux driver design decision).

A particular problem that I seem to face in this stage is fleshing out a broad ambiguous idea to come up with a concrete plan of action. This requires resolving the many ambiguities in design, implementation, and execution. Personally, I find myself stuck in the bog making relatively minor decisions - obsessively weighing pros and cons in an acute case of analysis paralysis. I have recently been tripped up by this twice in quick succession - over my summer internship, and over a hackathon last weekend.

In software terms, I simply can’t find the sweet middle ground between a very broad idea and diving into code - a recipe for numerous wrong turns, wasted time, and frustration. On the other hand, my software engineering class has fed me enough disaster stories of the ‘waterfall’ approach to make me averse to a very detailed planning stage. The promoted alternative, the ‘agile’ approach, promotes quick sprints of execution to take small iterative steps to the larger goal.

In practice, however, planning the sprints turns out to be a non-trivial task, with bad implementations of the process leading to prioritising locally optimal decisions (like small feature development) and ignoring larger, complex tasks (like refactoring). The trick seems to be making decisions that are atleast both locally and globally satisficing - the day to day cannot be ignored, but neither should the broader global role. However, managing this tradeoff is easier said than done.

A similar conundrum exists in managing personal time. Balancing commitments across classes and short-term concerns, and personal development, a (very) long-term one, has always been tough. This is especially exacerbated because most social and systemic feedback responds to short-term successes and defeats, while long-term development, rather tautologically, can only be recognized in hindsight.

I only hope managing these becomes easier with experience and perspective.

1</a>: civil servant, poet, one of the best teachers ever, object of my unabashed adulation.

tags: